How Hormone Fluctuations Influence Autoimmune Flares

Obie Editorial Team

Your menstrual cycle is more than just a monthly rhythm—it’s a window into your body’s complex immune system. Shifts in estrogen and progesterone don’t just influence reproductive health; they also affect how your body responds to inflammation, infections, and even autoimmune disease. For women living with chronic conditions like lupus, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or multiple sclerosis (MS), for example, understanding these hormonal-immune interactions can be a powerful tool for managing symptoms and optimizing wellness.

The Hormone–Immune Connection

Your immune system isn’t static throughout your cycle—it adapts. Estrogen, especially in the first half of the cycle (the follicular phase), boosts immune surveillance by increasing antibody production and reducing inflammatory markers. Progesterone, which dominates in the second half (the luteal phase), has a more anti-inflammatory and immune-suppressing role.

This balancing act supports reproductive functions, but for those with autoimmune disease, these shifts can trigger symptom flares or moments of vulnerability. According to Desai and Brinton (2019), the interplay between estrogen, progesterone, and immune regulation is a key factor in the female predominance of autoimmune diseases and the cyclic nature of symptoms experienced by many women.

Autoimmune Disease and Your Cycle

Women with autoimmune diseases often notice that their symptoms aren’t random—they follow a pattern tied to their menstrual cycle. Let’s look at how these patterns can play out in specific conditions:

Lupus (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus)

Many women with lupus report flares just before menstruation or during ovulation. These phases coincide with drops in estrogen or rapid hormone shifts, which may trigger immune overactivity in a disease already marked by excessive inflammation.

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

RA symptoms may improve during the high-estrogen phases but worsen just before or during menstruation, when progesterone and estrogen both decline. Some women also experience increased joint pain and stiffness during the luteal phase, when inflammation can become more pronounced.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

MS flares have also been linked to hormonal changes, especially the premenstrual drop in progesterone. Since progesterone has a protective, anti-inflammatory effect in the central nervous system, its absence may temporarily increase symptom severity or fatigue.

Practical Tips for Managing Cycle-Related Flares

Recognizing patterns in your symptoms across your cycle can help you anticipate and prepare for flares. Consider:

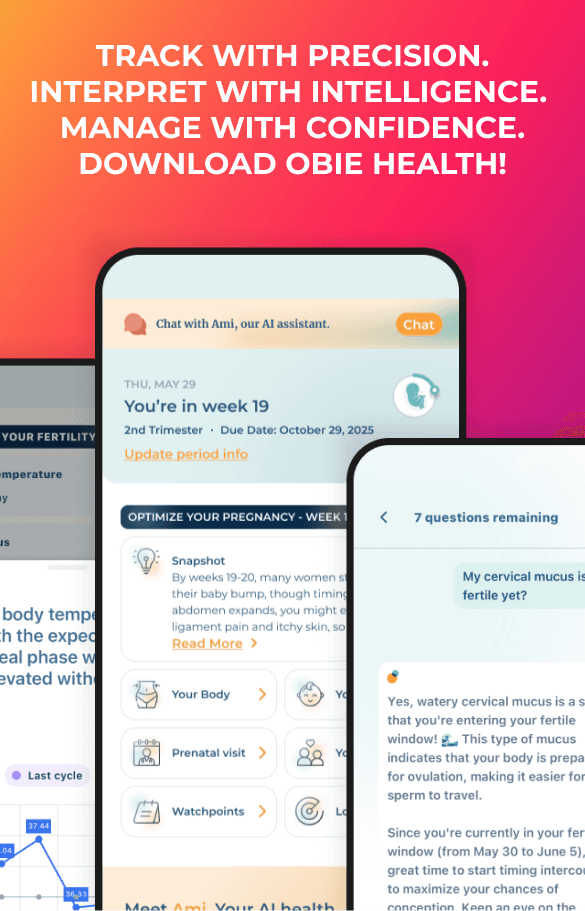

- Keep a symptom and cycle diary to track flare-ups, or use an app like Obie to help you track your cycle.

- Talking to your healthcare provider about adjusting medications around vulnerable times in your cycle

- Supporting immune health with consistent sleep, gentle movement, and stress management throughout your cycle

- Staying hydrated and prioritizing anti-inflammatory foods, especially during the luteal and menstrual phases

- Discussing hormonal treatments (like birth control or hormone modulators) with your provider if symptoms are severe or disruptive

Why This Matters

For too long, women’s immune health has been viewed as separate from reproductive health. But research now confirms that hormones play a central role in modulating immune responses—sometimes tipping the balance toward flare-ups, other times providing relief. By tuning into these shifts, women with autoimmune diseases can be more proactive, informed, and empowered in managing their health.

Source:

Desai MK, Brinton RD. Autoimmune disease in women: endocrine transition and risk across the lifespan. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:265. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00265